X-Men: God Loves, Man Kills review

A clever reference to Uncanny X-Men No. 134 in the Netflix original show Stranger Things got me thinking about X-Men again. It had me ruminating on the X-Men comics of the 80’s, an era in which Marvel’s mutants went from B-level superheroes to arguably the most important series in all Comicdom. This rise to prominence was mostly due to the revelatory writing of Chris Claremont, who helmed the X-Men books for 17 years (1975–1991) and set the stage for the explosive popularity of the X-Men cartoon series in 1992.

Specifically, I found myself wanting to revisit X-Men comics of the early 80’s, post-Dark Phoenix Saga, right around the time period Stranger Things takes place (1983). That’s when it dawned on me that I had never read God Loves, Man Kills, a standalone graphic novel from 1982. The book had received loads of praise from X-perts over the years, but I’d never really got around to reading it. (How I managed to avoid it for this long is beyond me.)

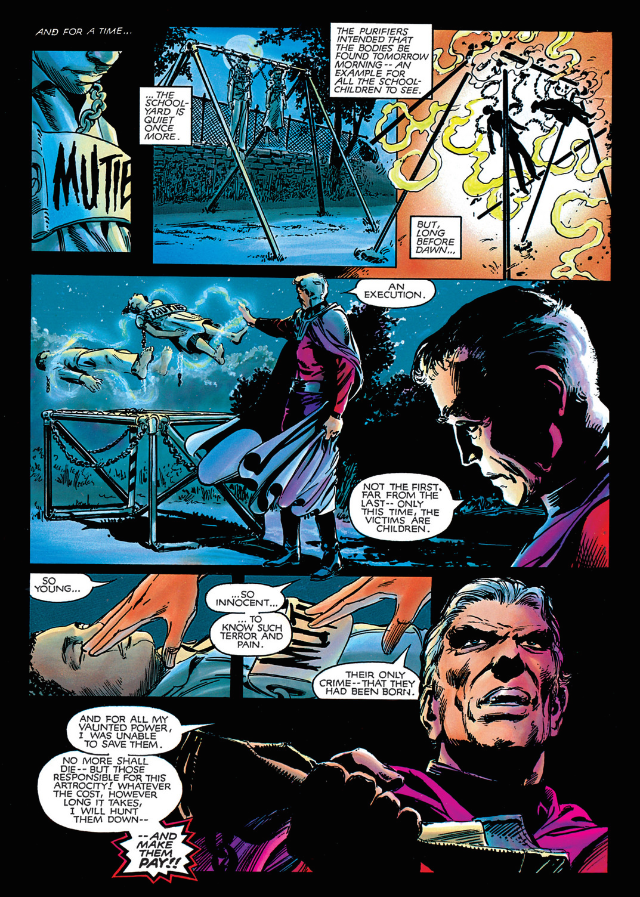

The story wastes no time, kicking things off with the chilling murder of two mutant children.

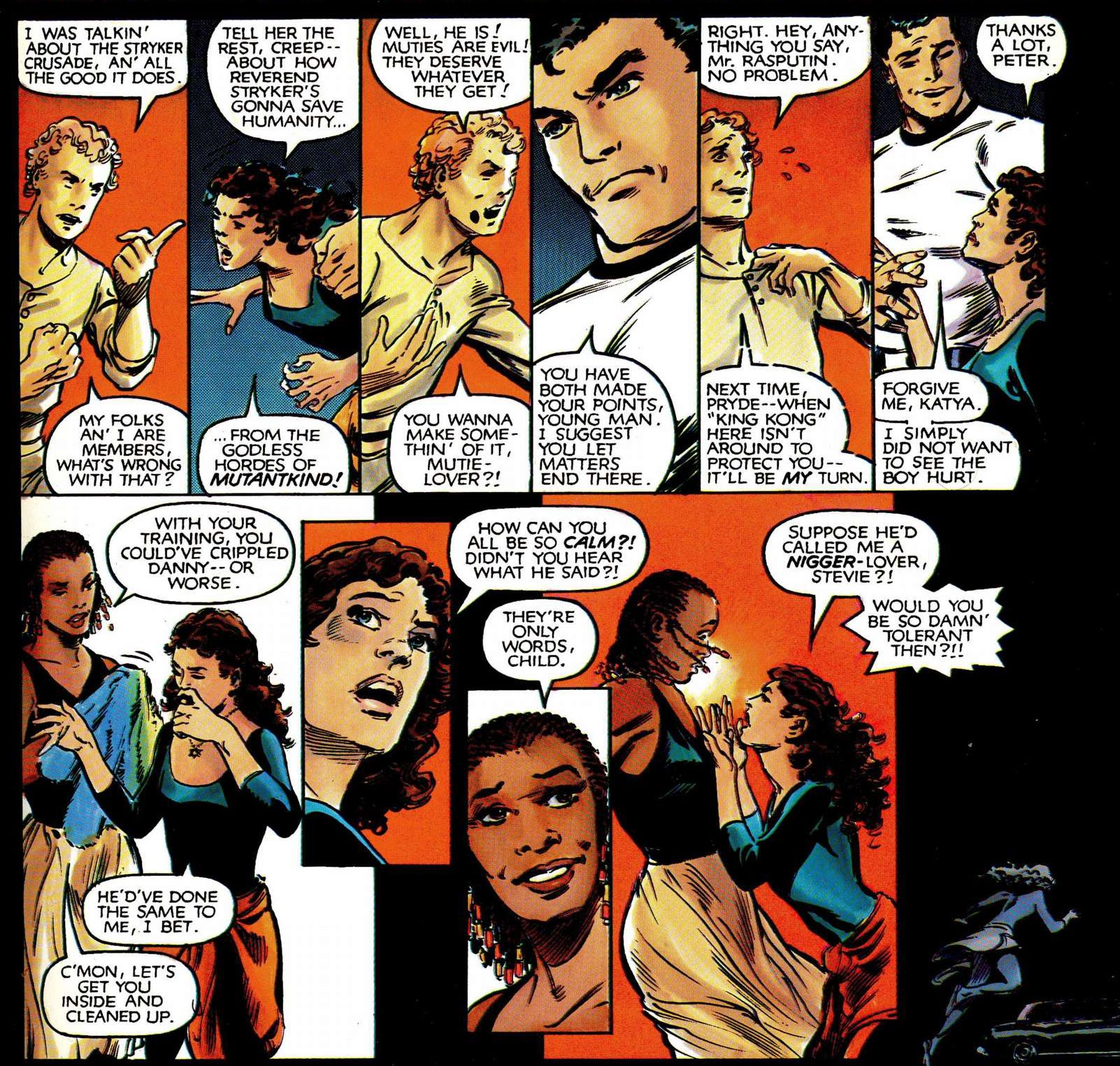

God Loves, Man Kills is really the prototypical X-Men tale, one that has informed the direction of the series ever since. The story takes the metaphor of anti-mutant prejudice as racism from subtext and makes it explicit, a rather ballsy move for early 80’s. Impressively, the story is so fully thought out and well written, it has aged amazingly well. Somehow, the politics of the story feel even more relevant today than they did back in the day it was written. Or so I would I imagine...I was only born in '83, after all.

The art here was done by Brent Anderson, a different artist than was penciling Uncanny X-men at the time. His style looks quite distinct from the mainline comic—a little less 'Marvel superhero' and a little more everyday realism. This art gives the graphic novel a unique feel, setting it apart and grounding it in time like a Norman Rockwell painting. This style was also reminded me of a fundamentalist Christian propaganda comic from 1976 that I had read just prior. The overlapping elements of extreme religious rhetoric and vaguely similar art styles made this book—a goddamn masterpiece by comparison—land that much harder for me.

God Loves, Man Kills tells the story of a religious conservative figure—a televangelist by the name of Reverend William Stryker—who shrewdly uses fundamentalist biblical interpretations and impressive skills of rhetoric to rally the public against the specter of mutant kind. A noteworthy element here is that Stryker wholeheartedly believes that mutants are wicked, that their superhuman abilities are not just dangerous, but the work of the actual Devil. He’s not the least bit disingenuous in his crusade. He feels he is morally right, doing God’s work. Stryker is compelled by his religious convictions to eradicate mutants for the good of the world.

So the villain of this story has no superpowers, can’t physically take on even one of X-men, let alone the whole team, and is essential Pat Robertson from the 700 Club. Doesn’t seem all that intimidating, right? And yet Stryker is perhaps the most dangerous enemy the team has ever faced because his fight is a political one; his weapons are moral superiority and fear. Stryker’s success doesn’t hinge on besting Colossus in a fistfight, he wins by influencing the public. This makes for not only a surprisingly mature basis for conflict in a comic, it’s also some plausibly scary shit.

This particular story also helps explain an important distinction between the X-Men—who are generally hated and feared by public in the Marvel universe—and the Avengers, Fantastic Four, Spider-Man, etc., who also have superpowers, but aren't pariahs. The difference in public image is the nature of mutation. The extraordinary and often dangerous abilities mutants are born with is one element of mutant fear, but only the surface layer of the hate the X-Men receive. The deeper layer is one of identity and tribalism. It's the fact that anyone—your friends, your partner, your children even—could be one of them, and you wouldn't necessarily know it. Mutation blurs the established lines of in-groups and out-groups by creating startling new criteria for those lines to be drawn.

This uncertain identity element of mutation is the true reason the X-Men are hated. The true fear is not what mutants might do to you, but what their existence means to your place in world. And if you should discover that you yourself are one of them, your status is suddenly the most precarious of all.

“Mature” strikes me as perhaps the most apt description of God Loves, Man Kills. I can easily see how this story might be appealing more to adults than the kids often associated with superhero fandom. It’s also super dark, though in a thematic way as opposed to excessive violence or gore. The ideas presented about prejudice, faith, morality, responsibility, control of the masses, etc. are legitimately thought-provoking. And since the main conflict of the story is ideological rather than physical, we even see a decisive blow of the final battle that doesn’t even come from a central character. (Oh uh, Spoilers! I guess…)

X-Men in this era had a great cast of characters with which to explore the intersection of these themes. As a Jewish teenager, Kitty Pryde reacts much differently to casual bigotry and mutant slurs than Piotr (Colossus), a young Russian with essentially no religion, as demonstrated in the panels below.

Nightcrawler, the X-man most demonic in appearance, is actually a devout Catholic, well-versed in faith and dogma. Old curmudgeon Wolverine pays no mind moral or religious debates, but pragmatically follows any shifts in public opinion that might affect mutant rights. Cyclops is at his best as the virtuous field leader, holding true to Xavier's dream of coexistence even beyond his mentor. Every character gives a different lens with which to view the growing public debate. Plus there's Magneto being Magneto, and you can't help but love that righteous anger.

While overall quite tremendous, I wouldn't say this book is perfect. For one thing, Claremont provides a rather shocking backstory for Reverend Stryker that is not only dark and jarring, but entirely unnecessary. (Basically, he used to be a military man. After crashing his car in the desert, his wife goes into labor and gives birth to a mutant. Horrified, Stryker murders the infant and his wife, and tries to commit suicide via car explosion, only to miraculously survive.) I'm sure the idea was give some insight into the character's personal tragedies, to show the intensity with which he meets adversity, or perhaps how far he'll go when he believes he’s doing God’s work, but good God, man…. The origin story they gave him only serves to detract from the character’s image as wholly moral figure, and that's what makes the masses follow his lead. There are also a few death fake-outs in the book that, while brief, feel superfluous and silly.

On the art side, a few of Anderson’s pages are difficult to follow, with some strange transitions between panels. Generally, it’s very easy to tell what’s happening from one scene to the next, but there are a couple moments where things get a bit messy, panels that get a bit too action-packed and require considerable effort to decipher what has actually happened in the chaos. Despite these minor flaws, the art is quite good overall and feels well-suited to this particular story.

And the climax is very well executed.

I suppose it’s also worth noting that God Loves, Man Kills was loosely adapted into Bryan Singer's second X-Men film…uh, very loosely. As well-regarded as that movie generally was, it in no way does this story justice. Like most X-Men movies, X2 suffers from way too much Wolverine. And even though they did manage to get Nightcrawler in there, their version of him is such a joyless, moping, self-hating downer, he barely resembles the cheery swashbuckling acrobat from the comics. For shame, Bryan Singer. For fuzzy elf shame.

Reading this story in 2016 was surreal, because it actually feels more relevant than ever. The book seems like a cautionary tale about our country’s current political climate—or perhaps, the globe’s political climate—and yet it’s 34 years old. Prejudice towards an outcast minority, fear mongering by a conservative icon, the leveraging of religion to gain political power, casual bigotry boiling to surface and suddenly becoming a focal point of public discourse—the echoes to today’s reality are dishearteningly apt.

So if you only read one X-Men story—OK, maybe you should go with the Dark Phoenix Saga, that one is universally praised. But if you only read two X-Men stories, make sure you check out God Loves, Man Kills. It's scary for all the right reasons.